Oor elitisme (ek kan net hartlik saamstem):

"For of course I am completely an elitist, in the cultural but emphatically not the social sense. I prefer the good to the bad, the articulate to the mumbling, the esthetically developed to the merely primitive, and full to partial consciousness. I love the spectacle of skill, whether it's an expert gardener at work, or a good carpenter chopping dovetails, or someone tying a Bimini hitch that won't slip. I don't think stupid or ill-read people are as good to be with as wise and fully literate ones. I would rather watch a great tennis player than a mediocre one, unless the latter is a friend or a relative. Consequently, most of the human race doesn't matter much to me, outside the normal and necessary frame of courtesy and the obligation to respect human rights. I see no reason to squirm around apologizing for this. ... I hate poplulist kitch, no matter how much the demos loves it. To me, it is a form of manufactured tyrrany." - All The Things I Didn't Learn, bl. 31.

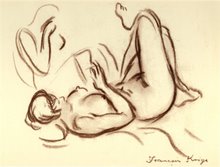

Oor Norman Lindsay, Australiese kunstenaar en algemene swaap:

"Except in isolated cases, Lindsay's imagery is too naïve to bear comparison with the mannered but very real sense of romantic evil which the pale horrid Liliths drawn by his nearest English equivalent, Beardsley, exhale. Lindsay's melon-breasted, ham-thighed Playmates are wholesome and dated. Their eroticism is depersonalized and cow-like; the very embodiments of adolescent sexual fantasy as it was in the days before teenagers were allowed to go to bed together, they smirk and pout and wiggle their elephantine buttocks but never become human; they are no more than the furniture of an escapist, a provincial rococo day-dream. Lindsay lived in a pantomime world of cavaliers, troubadours, Greek gods, courtiers, imps, panthers and magi; his art was a costume party." - The Art of Australia, bl. 84.

Oor die beeldspraak i.v.m. die Hemel (my mede-Amerikaners in The South sal nooit verstaan nie):

"Our modern ideas of Heaven and Hell are diluted. Heaven is vaguely thought of as a stretch of blue sky, with pearly gates like those in a hairdresser's movie ad, harps, clouds, and angels in long white caftans flapping their technicolour wings in time with the strains of Mario Lanza wafted faintly through some celestial Muzak system. It is all as clean as the inside of a new ice-box and to anyone with a trace of blood in his veins it a prospect of appalling boredom, like being confined forever in Disneyland with nobody to talk to but Norman Vincent Peale and the dithering secretary of the local Methodist Ladies Bridge Auxiliary." - Heaven and Hell in Western Art, bl. 7.

Oor gatpyn hedendaagse kunstenaars:

"For nearly a quarter of a century, late-modernist art teaching (especially in America) has increasingly succumbed to the fiction that the values of the so-called academy - meaning, in essence, the transmission of disciplined skills based on drawing from the live model and the natural motif - were hostile to 'creativity'. This fiction enabled Americans to ignore the inconvenient fact that virtually all artists who created and extended the modernist enterprise between 1890 and 1950, Beckmann no less than Picasso, Miró and de Kooning as well as Degas and Matisse, were formed by the atelier system and could no more have done without the particular skills it inculcated than an aircraft can fly without an airstrip. The philosophical beauty of Mondrian's squares and grids begins with the empirical beauty of his apple trees. Whereas thanks to America's tedious obsession with the therapeutic, its art schools in the 1960s and 1970s tended to become crèches, whose aim was less to transmit the difficult skills of painting and sculpture than to produce 'fulfilled' personalities. At this no one could fail. Besides, it was easier on the teachers if they left their students to do their own thing." Nothing If Not Critical, intro.

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment